Get in touch

555-555-5555

mymail@mailservice.com

Articles

30 Nov, 2023

Trigger warning: This article discusses suicide and suicidal thinking. If you are suicidal, call 988; Go to your nearest hospital emergency room; or Text HOME to 741741 for 24/7 crisis support. “I wrestle alone in the dark, in the deep dark. And that only I can know, only I can understand my own condition. You live with the threat, you tell me you live with the threat of my extinction. Leonard, I live with it too. This is my right; it is the right of every human being.” Virginia Woolfe Mrs. Dalloway/The Hours “Come on, come on; I see no changes, wake up in the morning and I ask myself is life worth living, should I blast myself.” Tupac Changes Stephen ‘tWitch’ Boss’ tragic suicide continues to be minutely dissected to determine if there were warning signs that he was suicidal. As with other high profile people who have died by suicide, why looms large. Why would intelligent, accomplished, and seemingly vibrant people end their lives? However, why is not the only question that should be considered. In the aftermath of a completed suicide, family, friends, and others are left wondering how. How did they miss so called red flags or warning signs that suicide was immient? How do we collectively and individually help family members forge a path forward after a loved one dies by suicide? Within hours of Mr. Boss’ death, news stories on red flags or warnings that a person is suicidal proliferated across the airwaves and social media. Though well-intended, these news stories ignore STIGMA, the overarching reason that people with lived experience do not tell anyone that they are suicidal. That same STIGMA is no respecter of persons or geography. It exists regardless of country, gender, religious affiliation, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. In certain circles, such as the legal profession, the words mental illness, suicide, and suicidal thinking are still too stigmatized to convene candid conversations. I am not a celebrity. I am a high functioning black woman, attorney, mother, and person of faith who has lived with depression for at least 45 years with insidious episodes of suicidal thinking generously peppered throughout. Like many of my peers, I am extremely adept at concealing my depression and suicidal thoughts. Because I keep persisting as a black woman, attorney, and mother, few people, if any, know when I am wrestling with depression and suicidal thoughts alone in a dark place. They also don’t know that there are still mornings when I want to blast myself to bits before getting out of bed. Fortunately these episodes have greatly diminished giving my mind a well deserved rest. I rarely share such intimate details because: 1. I want to protect you. 2. I don’t want you to freak out. 3. You have your own problems.4. I cannot carry your emotional weight, fear, and guilt. 5. I don’t trust you. 6. You judge me and don’t believe that mental illness is a brain disease. 7. You don’t trust me or my ability to manage my mental health. 8. You will call the police or attempt to have me placed on a 72 hour hold.* 9. I can decide if I am a danger to myself or others. 10. I know that my depression and suicidal thoughts make you uncomfortable. Choosing to die by suicide or not is solely my decision. The contradiction is that I really don’t want to end my life. For me suicide and suicidal thinking are about permanently turning off the voice that tempts and dares me to end my life. You may stop me from killing myself. But, the harsh truth is that if I want to die by suicide, I will. So, you may wonder how to help people with lived experience who are struggling with depression, suicide, suicidal thinking or all three. Storytelling is transformative. Tell your story. Pray for guidance, healing, mental clarity, and peace. Join or lead efforts to eliminate the fear, stigma, and shame surrounding mental illness and suicide. When writing about or reporting on mental illness and suicide remember that there may not be signs, red flags, or simple answers. Dive deeper. Don’t be afraid of telling the good, bad, and ugly parts of mental illness and suicide even if the ground shakes beneath your feet. You never know who is watching, reading, or listening. *A 72 hour hold is an involuntary mental health hospitalization imposed when it is determined that a person is a danger to themselves or others. MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES For non-emergency peer assistance, mental health awareness and education call the NAMI National HelpLine at (800) 950–6264 or text HelpLine to 62640 from 10:00 AM to 10:00PM. or American Society for Suicide Prevention https://www.afsp.org If you are suicidal or in crisis : Call 988 the new Suicide Crisis Lifeline Go to your nearest emergency room or Text HOME to 741741 for 24/7 crisis support. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1–800–273-TALK (8255)

29 Nov, 2023

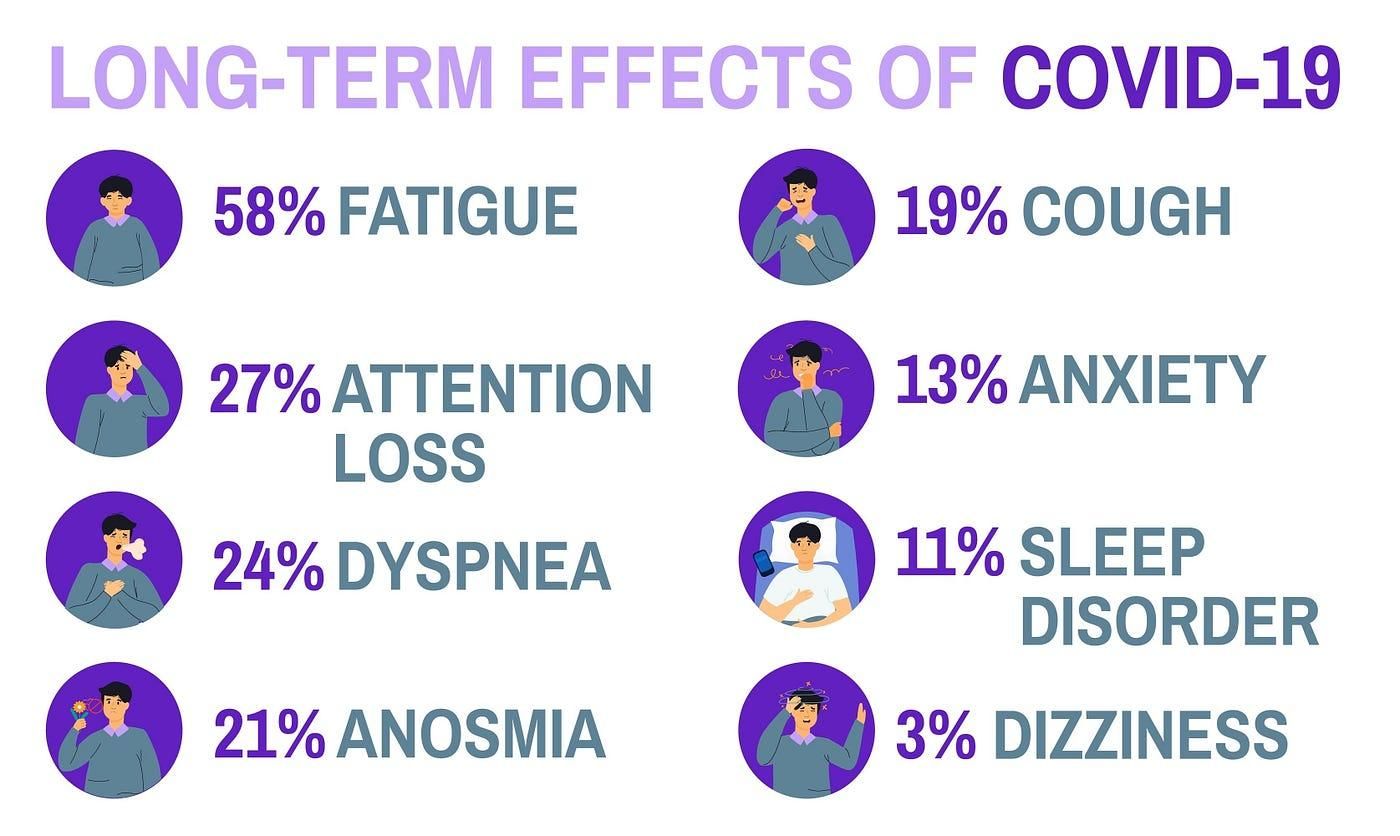

I dreaded change. Change is inconvenient, disruptive, and hardwork. It sets me on paths that I do not want to travel. Occasionally, that path includes feeling my way around in the dark. Change forces me to navigate the constantly shifting landscape that often comes with it. In my experience, transformational change happens in life’s hard places. Three of these hard places changed me and shaped my perspective on change itself. I entered the first of the three hard places in February 2006. During that month, I started over with two children, two months of outstanding mortgage payments, an empty refrigerator, and $120.00. My marriage was over and I joined the community of solo mothers raising children alone with little to no support. This was not what I signed up for. I was raised by two parents in a solid middle class suburb. I at tended excellent schools and had other advantages that most children did not. As a solo mom, I felt ill-equipped to support my children and provide what they needed. I was so focused on supporting my children’s adjustment to our new normal, that I did not realize that I was in a hard place. A hard place is also known as a valley or wilderness experience. My personal and spiritual work is usually done in life’s hard places. Experience has taught me that I will not transition out of the hard place/wilderness/valley if I do not learn the lesson or do the work. This hard place revealed that I was deeply depressed for nearly my entire 14 year marriage but did not know it. I have had bouts of depression since I was at least 15 years old. At that time, I did not have the language or understanding to tell my parents how I felt. During my late teens and twenties, my depressive episodes were relatively mild. Without a formal diagnosis I learned what would trigger a depressive episode and how to quickly cycle out of it. However, the depression that I uncovered in 2006 was a raging out of control beast that required ongoing medical treatment and medication. Initially, I denied the ferocity of my depression and would not take my antidepressants as prescribed. The consequences were brutal and exacted an extremely high price. Backed into a corner I had a choice: responsibly manage my mental health or continue down a dangerous and destructive path. My children needed me to be mentally and emotionally healthy. So I chose to prioritize my mental health and have never looked back. Because of my educational and professional credentials, I thought that it would not be difficult to secure a job with a regular paycheck and health insurance. Despite my best efforts, I could not find a job. So I doubled down, expanded my network, and refined my job search. At the end of each successive year, I found myself back where I started the previous January. It took me until January 2013 to realize that I could pause and do the work or spend another year in the wilderness walking around the same circle. On June 12, 2020, I started another journey through another hard place. That evening my father stood up, suddenly collapsed, and then died shortly after he finished eating dinner with my mother. It was the weekend of my parents’ 62nd wedding anniversary. My family is very, very small. At the time, I and other family members were in or en route to Atlanta for my aunt’s funeral. That weekend my assignment was twofold: support my cousin as she buried her last remaining parent and represent my parents who were too elderly to fly or drive 800 plus miles to Atlanta especially in the midst of the COVID19 pandemic. I was in Atlanta and spoke to my father several times that day including shortly before he died. How could my father be alive and then dead only a few hours later. Early the following morning, I called a friend from church to inform her about my father’s death. I told her that I could not stay for my aunt’s funeral and was leaving immediately to be with my mother. My friend said that I couldn’t leave because my assignment was incomplete. She was right. I traveled to Atlanta to support my cousin and stand in for my parents. My brother and other family members left Atlanta and rushed home to be with my mother. So I stayed. Somewhere deep inside myself I found the strength to be fully present for my cousin. My father and aunt died within the first two weeks of June. While my mother is still very much alive, losing two elders in quick succession changed the dynamic of my very small family. With my father’s death we lost our family patriarch and go to person for almost everything. The deaths of my aunt and father accelerated my transition into the role of family elder. My days of only performing tasks assigned by family elders are numbered. As the oldest, I must ensure continuity after my mother transitions. Death and mortality have set me on a well worn path that I do not want to travel. There I will process my own grief, discover who I am without parents, and come to terms with my mortality. Ten years ago I would not have had the perspective and fortitude to follow this path or do the work. I am still on the journey through my latest hard place. A few years ago, I started thinking about winding down my professional working life. I thought that I could finally run away from my young adult children, buy a Vespa scooter, and spend several months in London. Then two years ago this month I hit a detour that set me on yet another path that I do not want to travel. On December 3, 2020, I was diagnosed with COVID19. I was released from quarantine a few days before Christmas and slowly resumed my regular schedule. Then in February 2021, new COVID19 symptoms appeared and old ones rebounded. Eventually I was diagnosed with what is now called Long COVID. More than two years later Long COVID is still widely unknown. It is a group of new or returning COVID19 symptoms that can last months and even years. It can cause multisystem organ damage affecting the heart, kidneys, skin, respiratory system, and brain even in people with no prior history of these conditions. Some people with Long COVID develop extremely serious and life threatening medical conditions. Some experience disruptions in regular bodily functions like the menstrual cycle. My own Long COVID symptoms include cognitive impairment also known as brain fog, extreme fatigue, difficulty breathing, neurologic dysfunction, and inflammation throughout my body. I also suffer from Post-Exertional Malaise also known as PEM. This means that I am easily overexerted. It can take weeks and even months to recover from the slightest overexertion. By August 2021, I was in such ragged shape that I finally agreed to take short term disability leave. After 11 months on short term disability leave, I was forced to acknowledge that I could no longer perform my job duties because of Long COVID. Since I could not return to work full-time, I was involuntarily separated from employment due to disability. At that time, I lost the comprehensive health insurance and other benefits that I desperately needed to cover my medical care. I had to apply for disability and purchase health insurance on the Market Place which severely limits my access to health care providers. My own recovery is slow and often lonely. I have endured painful and frustrating setbacks. There are still a few dark days when it feels like I will not survive. This year I completed my sixth decade around the sun. My future is uncertain. I do not know if or how long I will be able to work. So I have temporarily shelved my plan to buy a Vespa scooter and run away to London. My journey through the hard place called Long COVID has been difficult, overwhelming, and sometimes scary. But I am determined to follow the path that I do not want to follow as it unfolds before me. Do not pity me because I have Long COVID. I am not special. It is just another hard place that has changed my trajectory. We all have hard places. I intend to use my foundational tools to navigate Long COVID. Change is part of life. The following are my foundational tools for navigating change and transitions: Armor. Faith. Fearlessness. Focus. Gratitude. Humility. Mindfulness. Patience. Prayer and Meditation. Readiness. Self care. Self-compassion. *This article was presented at the 2022 ABA 16th Annual Labor and Employment Law Conference

28 Nov, 2023

As a black woman, attorney, and single mother living with depression, I thought that I had little besides race in common with black men with the same mental illness. Then I saw Fences the movie adapted from the play by August Wilson. In Fences , Troy Maxson is a fifty-three year old black man working as a garbage collector. Troy played baseball in the Negro Leagues and even did a stint in prison. I was immediately drawn to Troy because he wore a “big apple” hat. My father and other black men in and around Troy’s generation wore these hats. Troy represents every black man in America struggling to be respected in the midst of the desolation that comes with living in a country that refuses to see him as human. On the surface, Troy is tough, blunt bordering on harsh, stubborn, and hypocritical. However, to dismiss Troy as one more angry black man who had an extra-marital affair that resulted in a child with a woman who is not his wife misses the source that is, at least in part, driving his behavior. Perhaps it was Denzel Washington’s amazing ability to step into the skin of the character, but as the movie unfolded it became increasingly clear that Troy’s hardness was actually a mask that hid his fragility, pain, and depression. The American Psychiatric Association estimates that between five and ten percent of black men live with depression. This statistic is further compounded by the fact that within the black community depression remains the word that must not be named. Historically black men have not had a safe space to acknowledge their depression and seek the necessary treatment. They birthed other generations of black men who grew up believing that they had to compartmentalize their depression and bury it deep inside. Left untreated, depression grows into an unruly garden filled with weeds and thorns. Some black men use drugs and alcohol to blunt the physical and emotional pain that comes with depression. Others are so weighed down with hopelessness that they see suicide as their only means of escape. This is where my path intersects with black men who live with depression. I have lived with depression for at least thirty-nine of my fifty-four years. Like Troy Maxson, I wore a mask to hide my depression. I did not tell anyone that I was depressed or that my mind lived in that gray space of suicide. As a result, my depression and constant thoughts of suicide became normal. I became expert at navigating my depression and suicidal thoughts along with daily responsibilities. My so-called coping skills worked until February 2006. Eleven years ago, I experienced a major life shift that knocked my mask askew and exposed my depression. With that major life shift came the realization that I had been beyond clinically depressed for at least a decade. My depression was laid bare for everyone including my children to see. I had to find new ways of managing and treating my condition. This started with accepting my need for medication to treat my depression. I formed a “kitchen cabinet” of people who hold me accountable for following my treatment plan so that I am mentally strong enough to resist the voices inside my head constantly telling me to end my life. Eventually, I became strong enough to tell my story about living with depression. Looking through Troy Maxson’s lens, I now realize that for black men their depression is just as painful, isolating, and soul sucking as mine. Like me, black men have attempted suicide or are bombarded daily with suicidal thoughts. The difference is that as a black woman it is more acceptable for me to tell my story out loud. Now when I tell my story, I intend to speak truth to power for those who keep persisting through their depression. At the same time I will stand in the gap for black men like Troy Maxson who cannot talk about their depression and those who see suicide as their only means of escape. So, I leave you with my personal mantra for telling my story about living with depression is #noapology #noretreat #nosurrender

27 Nov, 2023

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, Long COVID potentially affects between 7.7 and 23 million Americans. I am one of those millions. On December 3, 2020, I was diagnosed with COVID19. In February 2021, some of my COVID19 symptoms rebounded and I was subsequently diagnosed with what is now called Long COVID. By the beginning of August 2021, my health had further deteriorated. I finally acknowledged that I would not recover from Long COVID unless I took time off work. So I relented and took short term disability leave. The New England Journal of Medicine called Long COVID America’s next national health disaster. According to the Brookings Institute roughly 16 million Americans of working age have Long COVID. Of that number 2 to 4 million cannot work due to this often debilitating condition. This has resulted in lost wages of approximately $170 billion dollars leaving long-haulers and those depending upon us in financial peril. I am extremely concerned about our capacity to manage and support those living with Long COVID. So I am issuing a clarion call for a community wide reckoning. That reckoning starts with understanding what Long COVID is. Long COVID is a group of new or returning COVID19 symptoms that can last months and sometimes years. Nearly all long-haulers suffer from extreme fatigue. Long COVID can cause multisystem organ damage affecting the heart, kidneys, skin, respiratory system, and brain even in people with no prior history of such damage. Some people with Long COVID develop dangerous blood clots. Others are struggling with other serious conditions such as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome also known as ME/CFS, strokes, and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome commonly known as POTS. Some female long-haulers experience changes in their menstrual cycle. My own Long COVID symptoms include cognitive impairment also known as brain fog, extreme fatigue, difficulty breathing, neurologic dysfunction, and inflammation throughout my body. I also suffer from Post-Exertional Malaise also known as PEM. This means that I am easily overexerted. Eighteen months in I continue to be crushed by fatigue, struggle cognitively, still cannot taste or smell, and have PEM. Long COVID has completely upended my life. I rarely leave home and must closely pace myself to avoid overexertion. Everyday is a balancing act. I must carefully allocate my limited energy. Sometimes I must decide if I am going to cook dinner, shower, or do laundry. On the days that I have pulmonary maintenance, I cannot cook or take a shower. Pushing myself to do more results in overexertion. In June 2022, I pushed too hard. I have been mostly bedridden since then. Long COVID has kicked my tale for the last 547 days with no signs of stopping. My own recovery is slow and often lonely. I have endured painful setbacks. There are still dark days when my death seems imminent. Despite these obstacles, I was determined to return to work. After one year on short term disability leave, I was forced to acknowledge that I could no longer perform my job due to Long COVID. Because I could not return to work full-time, state law mandated my involuntary separation due to disability. The one consistent bright spot is the outstanding medical care that I receive as a patient in the Post COVID Recovery Program at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Fortunately I was an early patient in the program. It is the only such program in Columbus. All Long COVID patients are not as fortunate. They are navigating scary symptoms within systems that, though well-intentioned, do not have the capacity to help them. The news is not all bad. Recently the Biden Administration created an office specifically focused on Long COVID. The office is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The function and goals of this office are detailed in the two reports released by the administration. Links to these reports can be found below. Additionally, in July 2022 the US Department of Labor initiated a virtual dialog with and solicited ideas from the public on how to support workers with Long COVID in the workplace. The comment period has ended. Long COVID is no respecter of persons. It affects millions of Americans regardless of race, gender, age, socioeconomic status, or geography. Long COVID has compromised my health, quality of life, and economic security. It destroys careers and has forced sufferers to quit or retire early. We need to develop a comprehensive plan to address Long COVID. So I am issuing a clarion call. Directly or indirectly, Long COVID impacts all of us. This is my clarion call about Long COVID. We have work to do. Originally published in Columbus Underground.

26 Nov, 2023

December 3, 2020 marked twelve months, three hundred sixty-five days, or five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred minutes of living with COVID19 and now Long COVID. It has been one of the most difficult periods of my life. By nature, I am a fighter. I fought COVID19 and now Long COVID every single day of the last twelve months. There were many days where I did not believe that I would survive. This is my story. But first an explanation and definition. Research indicates that most patients will recover from COVID19 without complications. However, COVID19 symptoms have rebounded in ten to twenty percent of patients weeks or months after initial infection. These patients are sometimes called long-haulers and suffer from Long COVID. The World Health Organization defines Long COVID as a condition that “occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 usually three months after the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms that last for at least two months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis.” Long COVID has been called a multi-system condition that can affect the body’s cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, sensory, pulmonary, and cognitive functions. As a solo mom and attorney, I have powered through illnesses regardless of how I felt because I had to. It is just the way that I am built. That changed on December 3, 2020 when I tested positive for COVID19. Within a few days of diagnosis my doctor ordered a Regeneron infusion to decrease the likelihood that I would be hospitalized. While I dodged hospitalization, my body still felt the full weight of the coronavirus. My blood oxygen level dropped. I slept nearly all day and night for days. I did not have the energy to climb the stairs and had to rest between the staircases in my home. Even basic tasks like taking a shower left me depleted and forced me back to bed. I was released from quarantine a few days before Christmas. At that time, I assumed that I would seamlessly resume my regular schedule of activities. I was wrong. When I was diagnosed with COVID19, I had a regular Bikram yoga practice. Because Bikram is a demanding form of yoga, I decided not to return to class until the end of January 2021, one month after I was released from quarantine. On February 14, 2021, I went to my yoga class. At the end of class I could not get up after the last pose. My entire body felt like lead. Eventually, I managed to stand up. When I returned home, I went to bed and stayed there for three straight days. In hindsight, I realize that this incident marked the arrival of Long COVID. I tried to return to Bikram yoga multiple times but could not finish a class. In the end, I stopped going all together. I have a very demanding job. Because of the pandemic, I work from home. During the months after I was released from quarantine, I attributed my debilitating fatigue to a grueling work schedule. Weeks later I began to experience other symptoms like difficulty breathing. Mild exertion left me winded and gasping for air. I must always carry an albuterol rescue inhaler. Because of my symptoms, I was referred to the Post COVID Recovery Clinic at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. At my first appointment in May 2021, my clinic doctor was so concerned about my condition that he wanted me to work part-time for three to six months. I knew that working part-time for an extended period was a nonstarter for my employer. At that time, I resisted applying for short term disability leave. As I had with other illnesses, I lowered my head and tried to power through Long COVID. Pulmonary testing revealed that COVID19 weakened my diaphragm and other respiratory muscles. In July 2021, I began twenty-four sessions of pulmonary rehabilitation to strengthen my pulmonary function and increase capacity. Medical testing further showed that COVID19 and Long COVID also affected my sensory and cognitive functions including my eyesight, ability to smell, and appetite. In late August 2021, my clinic doctor considered prescribing Aricept, an older medication used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, to alleviate my debilitating fatigue. Studies showed that Aricept eased the extreme fatigue experienced by many Long COVID patients. My clinic doctor also revisited the idea of taking an extended leave of absence from work so that I could begin to recover from Long COVID. I did not want to take another medication. So I relented and agreed to begin short term disability leave. In early October 2021, I completed pulmonary rehabilitation. I immediately began pulmonary maintenance to preserve the progress that I made in pulmonary rehabilitation. Although my pulmonary function has improved, sometimes I still have difficulty breathing. I continue to sleep for hours and spend most days in bed. I can only perform two or three tasks a day. If I push or overextend myself, I will spend several days in bed recovering. Large grocery stores, malls, and warehouses are often too much to navigate. To conserve my limited supply of energy I started using shortcuts like grocery delivery services. Recently, I started neurological rehabilitation to address fatigue and brain fog. My brain works overtime to compensate for other bodily functions adversely affected by Long COVID. This causes extreme fatigue and brain fog. Brain fog in Long COVID patients is akin to a concussion or other traumatic brain injury. As part of my neurological rehabilitation, I was prescribed Amantadine, an older medication formulated to treat Parkinson’s disease. Amantadine has alleviated brain fog and by extension extreme fatigue in some Long COVID patients. Thus far, Amantadine has only marginally reduced my fatigue. One year in, I am still on short-term disability leave. There are questions, such as those about my prognosis, that cannot be conclusively answered. For example, a number of Long COVID patients are unable to return to work. The jury is still out on whether I will be in that number. I do not know if I will fully recover from Long COVID or regain my pre-COVID health. So I work hard to mitigate the possible long term impact of Long COVID on my body. I always wear my mask, avoid large crowds or super spreader events, and stay inside as much as possible. I am fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot. I regularly go to pulmonary maintenance. I am a student of any serious medical condition or disease that I have. To that end, I joined the global Body Politic COVID-19 Slack Support Group. This support group birthed the Patient Led Research Collaborative, a group of Long COVID patients who are both intimately familiar with COVID19 and professionally research relevant subjects such as neuroscience, health activism, and human-centered design. The support group and collaborative were established to address the dearth of research on treating Long COVID. The COVID19 Support Group provides peer support, is a trove of information about Long COVID, and opportunities to listen to experts such as the NIH who share what they know about this condition. After twelve months, three hundred sixty-five days, or five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred minutes of living with COVID19 and now Long COVID there are five things that I know for sure: 1. There have been 802,000 deaths and counting due to COVID19 in the United States. 2. Long COVID is not a respecter of persons. People can develop COVID19 and/or Long COVID regardless of race, sex, religious affiliation, socioeconomic status, geography, and even political party or philosophy. 3. Having COVID19 and Long COVID are hard and solitary experiences. Everyday I fight for my health and well-being. 4. As with other catastrophes that affect the entire or wide swaths of the United States, we must work together as a country to successfully navigate the COVID19 pandemic. 5. To date, there is no cure for COVID19 and Long COVID. The pandemic will continue to evolve and sprout variants until we develop the resolve to work together.

25 Nov, 2023

Hello. My name is Stephanie. I am an attorney, writer, speaker, respectful disrupter and lifelong misfit living with depression I remember it like it was yesterday. Late one summer afternoon many years ago, a strange heaviness settled upon me. At the time, I was home alone. Like a phantom thread, that heaviness pulled me upstairs to my bedroom. Once there, I locked the door, closed the curtains and laid on my bed. The semidarkness of my bedroom covered me like a blanket. It was oddly comforting. I cannot remember how long I laid on my bed. When my family came home, I did not get up to greet them or respond when they called my name. Instead, I continued lying motionless on my bed. I did not move when I heard my father twisting the knob on my bedroom door. When my father finally unlocked and opened my bedroom door, I still did not get up or respond. He did not understand why I was lying on my bed in the dark. I did not know either. The year was 1978 and I was 15 years old. As a black teenager living in Cincinnati in the 1970s, I did not have the language to describe that strange heaviness. I certainly did not know that the heaviness was depression. Sometimes my depression is coupled with a strong desire to end my life. During these major depressive episodes or crises, my mind is flooded with thoughts of suicide. Once my mind is saturated, suicide starts calling me. Initially, suicide’s voice is a faint whisper. The voice steadily escalates, growing louder and more aggressive. It shifts into overdrive and tries to grind me into submission. My mind does not wrestle with suicidal ideation because it is defective or weak. For me suicide is not about wanting to die. Suicide casts itself as a quick and painless antidote to a pernicious depression. I know that suicide is anything but a viable solution. I understand that my completed suicide would reverberate throughout my family for generations. To overcome my suicidal ideation, I had to become a student of my mental illness. I learned what would trigger a depressive episode and how to quickly shut it down. This approach proved very effective until February 2006. In February 2006, I started over with two children, two months of outstanding mortgage payments, an empty refrigerator and $120. My marriage ended, and I started down the long, cracked path toward divorce. This seismic life shift caused me to regurgitate the pain, darkness, poor self-esteem, betrayal and worthlessness that I repeatedly swallowed throughout my 14-year marriage all over the ground. All that remained was a firmly entrenched depression that I had unwittingly lived with for nearly my entire marriage. The approach that proved so effective in my 20s was no match for this firmly entrenched depression. For the first time, I needed antidepressants to manage my mental illness. I must admit that I hate taking any type of medication. Prescribing antidepressants is not a straightforward process. It takes time. In my case, finding the most effective antidepressant was made more complicated because I was uninsured. My internist at the time started me on 10 mg of Lexapro, a dosage that gave me about seven good days a month. After about three months, my doctor increased my dosage of Lexapro to 20 mg daily. While helpful, it became apparent that Lexapro alone was not enough. It took several months to find a combination of medications that worked. When I felt better, my ego took over. I began what became a destructive cycle of taking antidepressants as prescribed for four or five months and then stopping because I felt better. This practice proved disastrous. Abruptly stopping antidepressants can trigger seizures and other serious conditions. Once the medications were out of my system I would mentally unravel and break down. Trust me, mentally unraveling is scary. I cry and completely fall apart. I become overwhelmed and can’t think straight. On a few occasions, I have even been suicidal. Eventually, I hit a wall and stop functioning in any meaningful way. As a single parent raising children entirely on my own, I did not have the luxury of falling apart. It took months of repeating this cycle over and over before I finally got tired of unraveling and all of the drama that comes with it. My depression is no different than any other medical condition that requires treatment. Today I still hate taking medication. But I have lived the ugly of what happens when I stop. I simply refuse to go out like that. Some of you may find my candor risky. Others may believe that my vulnerability will torpedo my legal career. However, after more than 40 years of living with depression, there are a few things that I know for sure. One, my silence will not help anyone. Two, I do not learn the lesson or do the soul work for my personal benefit. I have a responsibility to tell my story so that others on the same path know that they are not alone. Three, I will not heal what I refuse to acknowledge. The legal profession must stop pretending that the proverbial emperor is wearing clothes. Contrary to popular belief, we are merely human. We can zealously represent clients while embracing our humanity and vulnerability. As a community we can create emotionally safe spaces to discuss and seek treatment for a mental illness without being stigmatized. I am here to respectfully disrupt the stigma and shame associated with mental illness within the legal profession. My motto for living with depression is: #noapology #noretreat #noshame #nosurrender. Originally published in the American Bar Association Online Journal

22 Nov, 2023

“My son could have been in a gang, my daughter could have been pregnant. We defied all statistics.” My husband left in 2006. We’d been married thirteen years. He moved to another state and started a new family. I had $120, two kids, two months of outstanding mortgage payments, and an empty refrigerator. Back then I didn’t have family or friends nearby. My doctor said, “You’re beyond clinical depression.” I was tormented with the idea of suicide. I thought, “My children would be so much better off if I wasn’t here, because how can I be a good parent?” But actually, my children helped me the most. I wanted to stay in bed and hide. Because of my kids, I couldn’t do that. I’m a lawyer by profession, and I had to find a job with consistent benefits. My good friend helped me. Her husband had died very suddenly a few years before. She said, “There were days that I just did not want to get up. But I had to. No matter how hard it is, you’ve got to get up and just keep going, baby.” I had to let people know that I needed help. I had a hard time accepting that. One day my friend called and said, “I’ve got four hundred dollars for you to buy school clothing for your children.” I had to humble myself. If I didn’t humble myself and go to a food pantry or allow people to give me money, then we just simply weren’t going to make it. Every time I would hit a low point, I’d think, “There should be a manual that tells you how to deal with this.” That’s why in 2013 I decided to start telling my story to encourage other people. I’ve written about it in The Huffington Post, I’ve given a Tedx talk. That was a watershed year for me. Writing about my story is the work that gives me the most fulfillment. As a lawyer, I’ve seen real differences in how African American children are treated versus white children. I’ve seen inequality lead kids to join gangs, get pregnant at a young age. That could have happened to my children. But we defied all statistics. My son won a full college scholarship. He’s about to graduate, and he already has a job in Atlanta. My daughter is a high school senior. We hope she’ll get a scholarship too. When my husband left, my world had become incredibly narrow and small. Him leaving saved me. At the beginning I didn’t see it this way, but it freed me. Because of my journey over the last ten years, my world has become so big. --- Stephanie Mitchell Hughes is an attorney, writer, speaker, and respectful disrupter. She is a regular contributor to The Huffington Post, The Good Men Project, Thrive on Medium, and mariashriver.com. Watch Stephanie’s Tedx talk and follow her on Twitter and Facebook. Image Credit: Jeff Swensen/The Verbatim Agency for OptionB.Org

22 Nov, 2023

During the Valentine’s Day episode, you said that you wanted to “salute all the fat chicks out there celebrating their true love today which is food. You may be single now but you’ll catch mad discounts on chocolate tomorrow.” Charlamagne, I do not believe that you intended to insult more endowed women by calling us “fat chicks.” That said, you do not seem to appreciate the gravity of your remarks. You are also blithely unaware of the fact that for this “fat chick” and those like me your comments have consequences that extend beyond an episode of The Breakfast Club. Loving good food that sustains and nourishes the body is not wrong. Challenges arise when anyone consumes excessive amounts of any food be they overweight, skinny, or otherwise. I am a disordered eater who uses food and excess weight as a protective hedge against further trauma. I believe, quite wrongly, that my excess weight allows me to hide in plain sight. There are many so called “fat chicks” who use food and weight for the same reason. In some instances this behavior runs deep enough to constitute a serious and sometimes life threatening eating disorder. Breaking the pattern of my disordered eating has been a process that requires me to completely dig up and remove all traces of the lies that I accepted about myself. The lie that I am just an ugly girl unworthy of any expression of loving kindness. The lie that my physical body is merely an object to be abused instead of a sacred vessel deserving of protection. These lies have haunted me for as long as I can remember. I have repeatedly cast these lies off only for a triggering event to bring them roaring back. Charlamagne, as an radio personality and provocateur you know that words are powerful. I am certain that you do not want to say anything that only serves to trigger disordered behaviors or reinforce negative stereotypes about so called “fat chicks.” Going forward I challenge you to be provocative and mindful about what you say. As for me, I am on an exciting journey of discovery and healing where my weight loss is the byproduct of hard work. So, Charlamagne Tha God I am not a fat chick searching for mad discounts on chocolate. I am a woman working to live my best life. For more information about women and food I suggest the following all by Geneen Roth: Women Food and God Feeding the Hungry Heart When Food Is Love Breaking Free From Emotional Eating For help with an eating disorder contact the National Eating Disorders Association Helpline at: 1 (800) 931–2237

21 Nov, 2023

“Hello darkness, my old friend. I’ve come to talk to you again. . .” The Sound of Silence by Simon and Garfunkel On August 20, 2016, I posted the following comment on Facebook: “I need to confess a recurring thought that has troubled me all day and into the night. It is stopping me from sleeping. Confession holds me accountable for taking care of myself. My confession will terrify and worry several of you. But I need you to trust me enough not to freak out. Please don’t tell me that my life is worth everything. I know that. Don’t call the police, or my parents, or the Netcare Access Van. Please don’t show up on my doorstep. I just need to confess because stuffing my secret thoughts deep inside only feeds the insanity of wanting to harm myself. So here it goes. I am overwhelmed with depression. Though it does not happen everyday anymore right now I just want to lay down and die.” In 2013, when I finally emerged from a seven year slog out of my last depression pit, I vowed to never allow dark thoughts of suicide to hold my mind hostage again. So, last August while immersed in a full-blown depression crisis I decided to write my suicidal thoughts out loud on Facebook. I did not want these thoughts to become imbedded in my mind. I do not want death to begin stalking me daily as she did for many, many years. Writing my depression out loud holds me accountable for zealously guarding my mental health. It also freed up the space I needed to identify the source of my seemingly sudden depression crisis. My depression crisis was a red flag signaling that I was out of balance. The question was how and where? Was I overly tired or more stressed than usual? Had I overindulged in too many sweets or processed foods? Did I need a respite from the nonstop merry-go-round that is my life as a solo mom? Had my biochemistry changed making my current antidepressant regimen ineffective? My antidepressant medications had not been evaluated since my now former psychiatrist retired four years ago. Four years is an eternity in the world of antidepressants. Eventually, I identified my antidepressant regimen as the probable source of my crisis. Over the last four years, I have searched in vain for another psychiatrist or advanced nurse practitioner to manage and evaluate my medications. Every clinic and practice that I called told me that they were not accepting new patients. Why? Because there is a chronic shortage of psychiatrists across the United States that continues to worsen as the need for mental health services increases. The United States Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration has identified 4,000 communities across the country with a ratio of one psychiatrist for every 30,000 people. These 4,000 communities need roughly 2,800 psychiatrists to eliminate the shortage of mental health professionals. The factors contributing to this shortage include an aging profession where 59% of psychiatrists are 55 or older. Statistics also reveal that between 1995 and 2013 the number of psychiatrists only rose 12 percent while the U.S. population increased by 37 percent. Additionally, because of the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as Obamacare, more Americans are now eligible for mental health coverage. Inadequate pay, cumbersome insurance plans, and psychiatrists who only accept cash are all contributing factors. Finally, the fear, stigma and shame surrounding mental illness causes some medical students to view the field of psychiatry unfavorably. In my own case, the sudden onset of my depression crisis shook me to the core. I could no longer allow the dearth of mental health professionals to impede my search for a new psychiatrist. So once again I returned to and started working through my list of clinics and mental health practices only to be turned away because there was still no room at the proverbial inn. One clinic reported receiving between 35 and 45 calls daily from those seeking medication management. The intake professional at that clinic was horrified when I told her that my antidepressants had not been evaluated for four years. I then called two psychiatrists one of whom is a childhood friend for recommendations. She told me about one psychiatry practice with a waiting list of 600 people. A waiting list of 600 people is not a waiting list. I knew that a psychiatrist would evaluate me if I went to the emergency room. However, the question was at what cost. The price of seeing a psychiatrist in an emergency room raises the specter of a 72 hour hold. In short, I could be placed on an emergency 72 hour hold, meaning involuntarily committed to a psychiatric facility, if hospital officials determine that I am a danger to myself or others. For a solo mom parenting alone with no one to care for my children, an involuntary 72 hour hold is simply not a viable option. Most importantly, an involuntary commitment of any length is overkill for someone in need of medication management. Though not the focus of this post, suggestions for resolving the nationwide shortage of psychiatrists include intensive outpatient treatment, tele-psychiatry to evaluate patients via video across wider regions of the country and allowing mental health practitioners to work collaboratively with traditional healthcare providers. After two weeks spent culling through the list of mental health providers, I was able to schedule an appointment with an advanced nurse practitioner in a practice located two hours south of where I live. Seeing her would involve driving two hours each way after a full day of work. Such an arrangement is just not sustainable. Eventually, my insurer found a psychiatrist in my community who is accepting new patients. That said finding a new psychiatrist is only the beginning. Now my new psychiatrist and I must find a medication regimen that effectively treats my depression. Finding a psychiatrist in the midst of my depression crisis has been extremely overwhelming. But, protecting my mental health requires that I soldier on. Living in the darkness and silence that is the hallmark of my depression is no longer an option. My mantra for living with depression is #noapology #noretreat #nosurrender

Subscribe

Contact Us

Thank you for contacting us.

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Oops, there was an error sending your message.

Please try again later.

Please try again later.

Copyright © 2023 Stephanie Hughes

We trust Distinct with our Website because of their Unlimited Support, Client Testimonials, and Website Maintenance Checklist